To Sir, with Love

| To Sir, with Love | |

|---|---|

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James Clavell |

| Screenplay by | James Clavell |

| Based on | To Sir, With Love 1959 novel by E. R. Braithwaite |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Paul Beeson, B.S.C. |

| Edited by | Peter Thornton |

| Music by | Ron Grainer |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $625,000[1] or $600,000[2] |

| Box office | $42,432,803[3] or $22 million[2] |

To Sir, with Love is a 1967 British drama film that deals with social and racial issues in a secondary school in the East End of London. It stars Sidney Poitier and features Christian Roberts, Judy Geeson, Suzy Kendall, Patricia Routledge and singer Lulu making her film debut.[4] James Clavell directed from his own screenplay, which was based on E. R. Braithwaite's 1959 autobiographical novel of the same name.

The film's title song "To Sir with Love", sung by Lulu, peaked at the top of the Billboard Hot 100 chart for five weeks in the autumn of 1967 and ultimately was the best-selling single in the US that year; meanwhile, Poitier, playing a charismatic schoolteacher to troubled youth, was the first black actor to win a Golden Globe Award. The film ranked number 27 on Entertainment Weekly's list of the 50 Best High School Movies.[5]

The film premiered and became a hit one month before another film about troubled schools, Up the Down Staircase, appeared. A made-for-television sequel, To Sir, with Love II, was released in 1996, with Poitier reprising his starring role.

Plot

[edit]Mark Thackeray, an immigrant to Britain from British Guiana, has been unable to obtain an engineering position despite an 18-month job search. He accepts a teaching post for Class 12 at North Quay Secondary School in the East End of London, as an interim position, despite having no teaching experience.

The pupils there have been rejected from other schools, and Thackeray is a replacement for a teacher who recently died. The pupils, led by Bert Denham and Pamela Dare, behave badly: their antics range from vandalism to distasteful pranks. Thackeray retains a calm demeanour but loses his temper after discovering something being burned in the classroom stove, which turns out to be a girl's sanitary towel. He orders the boys out of the classroom, then reprimands all the girls, either for being responsible or passively observing, for what he says is their "slutty behaviour". Thackeray is angry with himself for allowing his pupils to incense him. Changing his approach, he informs the class that they will no longer study from textbooks. Until the end of term, he will treat them as adults and expects them to behave as such. He declares that they will address him as "Sir" or "Mr. Thackeray"; the girls will be addressed as "Miss" and boys by their surnames. They are also allowed to discuss any issue they wish. He gradually wins over the class, except for Denham who continually baits him.

Thackeray arranges a class trip to the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Natural History Museum in South Kensington which goes well. He later loses some support after defusing a potentially violent situation between his student Potter and the gym teacher, Mr. Bell. He demands that Potter apologise to Bell, even if he believes the latter was wrong. The group later refuses to invite Thackeray to the class dance. When mixed-race student Seales' white English mother dies, the class takes a collection for a wreath but refuses to accept Thackeray's donation. The students decline to deliver the wreath in person to Seales' house, fearing neighbourhood gossip for visiting a "coloured" person's house.

The headmaster tells Thackeray that the "adult approach" has failed, and future outings are cancelled. Thackeray is to teach the boys' gym classes until the headmaster can find a new permanent gym teacher. Meanwhile, Thackeray receives an engineering job offer in the post.

Pamela's mother asks for Thackeray to talk to her daughter about her behaviour at home. However, this annoys Pamela, whom Thackeray believes is infatuated with him. During a gym class, Denham challenges Thackeray to a boxing match. Thackeray initially declines but then reluctantly agrees. Denham delivers harmless blows to Thackeray's face, but the bout comes to an abrupt end after Thackeray’s lone punch is to Denham's solar plexus, which doubles Denham over in pain. Thackeray attends to Denham and then exits the gym unhurt, to the amazement of the class. Thackeray compliments Denham's ability and suggests he teach boxing to the younger pupils next year. Denham, impressed, expresses his admiration for Thackeray to his classmates. Thackeray regains their respect and is invited to the class dance. Later, while attending the funeral of Seales' mother, Thackeray is touched to find that his lectures on personal choice and responsibility have had an effect, and the entire class has attended.

At the dance, Pamela persuades Thackeray to be her partner for the "Ladies Choice" dance. Afterward, the class presents to Thackeray "a little present to remember us by." Too moved to speak, Thackeray retires to his classroom.

A rowdy couple enters the classroom. They mock Thackeray's gift, a silver tankard and card inscribed "To Sir, with Love" signed by the departing class, and goad Thackeray that they will be in his class next year. After they leave, Thackeray stands and rips up the engineering job offer, reconciled to the work he has ahead of him. He then takes a flower from the vase on his desk, places it in his lapel, and leaves.

Cast

[edit]- Sidney Poitier as Mr Mark Thackeray

- Judy Geeson as Pamela Dare

- Christian Roberts as Bert Denham

- Suzy Kendall as Miss Gillian Blanchard

- Lulu as Barbara "Babs" Pegg

- Faith Brook as Miss Grace Evans

- Geoffrey Bayldon as Mr Theo Weston

- Patricia Routledge as Clinty Clintridge

- Ann Bell as Mrs Dare

- Christopher Chittell as Potter

- Adrienne Posta as Moira Joseph

- Edward Burnham as Mr Florian, headmaster

- Rita Webb as Mrs Joseph

- Gareth Robinson as Tich Jackson

- Lynne Sue Moon as Miss Wong

- Anthony Villaroel as Seales

- Richard Willson as Curly

- Michael Des Barres as Williams

- Fred Griffiths as Market Stallholder

- Marianne Stone as Gert

- Dervis Ward as Mr Bell (P.T. Teacher)

- Fiona Duncan as Euphemia Phillips

- Mona Bruce as Josie Dawes

- Margaret Heald as Osgood

- Sally Cann as Schoolgirl

- Stewart Bevan as Schoolboy

- The Mindbenders as Themselves

- Nicholas Young (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Initially, Columbia was reluctant to hire Sidney Poitier or James Clavell, despite the interest which both expressed toward doing the film. (Clavell, aptly enough, had published The Children's Story just a few years prior.) Poitier and Clavell agreed to make the movie for small fees, provided Poitier got 10% of the gross and Clavell got 30% of the profits. "When we were ready to shoot, Columbia wanted either a rape or a big fight put in," said Martin Baum, Poitier's agent. "We held out, saying this was a gentle story, and we won."[2]

The film was shot in Wapping (including the railway station) and Shadwell in the East End of London, in the Victoria and Albert Museum and at Pinewood Studios.[6] The headmaster of the school where author Braithwaite taught, St George-in-the-East Central School (now the Mulberry House apartments)[7] adjacent to the north side of St George in the East church in Wapping, would not let the production film at that school.[6] The spire of the church is visible in the film, when Sir walks up Reardon Street, en route to the funeral for the mother of his student.[6]

Reception

[edit]The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "There is one shot in To Sir, With Love that shows Sidney Poitier staring into the sun through the window of his empty classroom with his arms spread out along the sill; in silhouette he looks for a second like Christ on the cross. The effect is almost certainly unintentional, but everything about James Clavell's sententious script ... suggests that he sees his hero as a Saviour figure, nobly sacrificing his own chance of middle-class respectability in order to redeem younger unfortunates from their hereditary taint of bad grammar and colourful language. Buttoned inside his immaculate white collars, Thackeray bravely shoulders the black man's burden, emitting a sanctimonious wince when confronted with any sign of moral weakness in others .... His comportment is infuriating, but no more so than the way in which the other characters respond to it. For if the film pretends to social realism by its frequent allusions to race prejudice, broken homes, ill-equipped classrooms and so on, its solutions have all the facile optimism of the most utopian folksongs. Thackeray's students all have hearts of gold, all aspire to self-improvement, all want "Sir" to approve of them. With scarcely a pimple or a genuine adolescent problem between them (there are no wallflowers at this school dance) they are all swept along to respectability on a great tidal wave of saccharine sentiment. Even the staff are moved by Thackeray's charismatic spell to a new sense of brotherhood. ... Nonetheless, within the limits imposed by the pious script, unimaginative photography and wooden direction, Christian Roberts and Lulu provide two very engaging performances."[8]

Upon its U.S. release, Bosley Crowther began his review by contrasting the film with Poitier's role and performance in the 1955 film Blackboard Jungle; unlike that earlier film, Crowther says "a nice air of gentility suffuses this pretty color film, and Mr. Poitier gives a quaint example of being proper and turning the other cheek. Although he controls himself with difficulty in some of his confrontations with his class, and even flares up on one occasion, he never acts like a boor, the way one of his fellow teachers (played by Geoffrey Bayldon) does. Except for a few barbed comments by the latter, there is little intrusion of or discussion about the issue of race: It is as discreetly played down as are many other probable tensions in this school. To Sir, with Love comes off as a cozy, good-humored and unbelievable little tale."[9]

Halliwell's Film and Video Guide describes it as "sentimental non-realism" and quotes a Monthly Film Bulletin review (possibly contemporary with its British release), which claims that "the sententious script sounds as if it has been written by a zealous Sunday school teacher after a particularly exhilarating boycott of South African oranges".[10]

The Time Out Film Guide says that it "bears no resemblance to school life as we know it" and the "hoodlums' miraculous reformation a week before the end of term (thanks to teacher Poitier) is laughable".[11] Although agreeing with the claims about the film's sentimentality, and giving it a mediocre rating, the Virgin Film Guide asserts: "What makes [this] such an enjoyable film is the mythic nature of Poitier's character. He manages to come across as a real person, while simultaneously embodying everything there is to know about morality, respect and integrity."[12]

The novel's author, E.R. Braithwaite, loathed the film, particularly because of its omission of the novel's interracial relationship, although it provided Braithwaite with some financial security from royalties. [13]

To Sir, with Love holds an 89% "Fresh" rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes based on 28 reviews.[14] The film grossed $42,432,803 at the box office in the United States, yielding $19,100,000 in rentals, on a $640,000 budget,[3] making it the sixth highest grossing picture of 1967 in the US. Poitier especially benefited from the film's success, for he had agreed to a mere $30,000 fee in exchange for 10% of the gross box office receipts, thus arranging one of the most impressive payoffs in film history. In fact, although Columbia insisted on an annual cap to Poitier of $25,000 to fulfill the percentage term, the studio was forced to revise the deal with Poitier when they calculated that they would be committed to 80 years of payments to him.[15]

Despite the character of Mark Thackeray being a leading role, the film has been criticised in modern times for Poitier's portrayal of the Magical Negro trope. Specific criticism of the portrayal was directed at the character's service as the sounding board and voice of reason for white antagonists.[16]

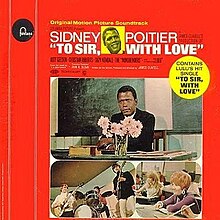

Soundtrack

[edit]| To Sir, with Love | |

|---|---|

| |

| Soundtrack album by various | |

| Released | 1967 |

| Genre | Traditional pop |

| Label | Fontana (UK) |

| Singles from To Sir, with Love | |

| |

The soundtrack album features music by Lulu, The Mindbenders, and incidental music by Ron Grainer. The original album was released on Fontana Records. It was re-released onto CD in 1995. AllMusic rated it three stars out of five.[17]

The title song was a Cash Box Top 100 number-one single for three weeks.[18]

- "To Sir With Love" (lyrics: Don Black; music: Mark London) – Lulu

- School Break Dancing "Stealing My Love from Me" (lyrics & music: Mark London) – Lulu

- Thackeray meets Faculty, Then Alone

- Music from Lunch Break "Off and Running" (lyric: Toni Wine; music: Carole Bayer) – The Mindbenders

- Thackeray Loses Temper, Gets an Idea

- Museum Outings Montage "To Sir, with Love" - Lulu

- A Classical Lesson

- Perhaps I Could Tidy Your Desk

- Potter's loss of temper in gym

- Thackeray reads letter about job

- Thackeray and Denham box in gym

- The funeral

- End of Term Dance "It's Getting Harder all the Time" (lyrics: Ben Raleigh; music: Charles Abertine) – The Mindbenders

- To Sir With Love – Lulu

James Clavell and Lulu's manager Marion Massey were angered and disappointed when the title song was not included in the nominations for the Academy Award for Best Original Song at the 40th Academy Awards in 1968. Clavell and Massey raised a formal objection to the exclusion, but to no avail.[19]

Awards and honours

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directors Guild of America Awards[20] | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | James Clavell | Nominated |

| Grammy Awards[21] | Best Original Score from a Motion Picture or Television Show | Ron Grainer, Don Black and Mark London | Nominated |

| Laurel Awards[22] | Sleeper of the Year | Won | |

| New Male Face | Christian Roberts[23] | Nominated | |

| New Female Face | Judy Geeson[24] | 2nd Place | |

Other honours

[edit]The film is recognised by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "To Sir With Love" – Nominated[25]

See also

[edit]- The Hindi film Imtihan (1974) starring Vinod Khanna as the teacher, and Tanuja as his love interest, was inspired by the film

- The Egyptian comedy Madrast Al-Mushaghebeen was inspired by the film.

- Up the Down Staircase, also released in 1967

- List of teachers portrayed in films

- List of hood films

References

[edit]- ^ "An author at home in Hollywood and Hong Kong". Dudar, Helen. Chicago Tribune. 12 April 1981: e1.

- ^ a b c A Blue-Ribbon Packager of Movie Deals Warga, Wayne. Los Angeles Times 20 April 1969: w1.

- ^ a b "To Sir, with Love, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ "To Sir, with Love". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ "50 Best High School Movies". Entertainment Weekly. 28 August 2015.

- ^ a b c "To Sir, With Love | 1967". movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "St George-in-the-East Church | Board Schools | Cable Street". stgitehistory.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

After the Second World War it became a secondary modern school, St George-in-the-East Central School… and has now been converted into 34 luxury apartments as 'Mulberry House'.

- ^ "To Sir, with Love". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 34 (396): 154. 1 January 1967 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (15 June 1967). "Poitier Meets the Cockneys: He Plays Teacher Who Wins Pupils Over". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Walker, John, ed. (1999). Halliwell's Film and Video Guide 2000. London: HarperCollins. p. 845. ISBN 0-00-653165-2.

- ^ David Pirie review in, John Pym (ed), Time Out Film Guide 2009, London: Ebury, 2008, p. 1098.

- ^ The Seventh Virgin Film Guide, London: Virgin Publishing, 1998, p. 729. Published by Cinebooks in the US. The "mediocre rating" claim is based on the authors giving the film three out of five stars.

- ^ Thomas, Susie (2013). "E.R. Braithwaite: To Sir, with Love". London Fictions. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "To Sir, with Love, Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Harris, Mark (2008). Pictures at a Revolution: Five Films and the Birth of a New Hollywood. Penguin Press. p. 328. ISBN 9781594201523.

- ^ "Obama the 'Magic Negro'". Los Angeles Times. 19 March 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ To Sir, with Love at AllMusic

- ^ "Top Single". Cash Box Magazine Charts. Cashbox. 1967. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Lulu: I Don't Want To Fight. Sphere Books (2 Dec. 2010) Paperback Edition. ISBN 978-0751546255

- ^ DGA 1967. Dga.org. Retrieved on 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Grammy Awards (1968)". IMDb.

- ^ "To Sir, with Love". IMDb.

- ^ "Christian Roberts". IMDb.

- ^ "Judy Geeson". IMDb.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 5 August 2016.

External links

[edit]- 1967 films

- 1960s coming-of-age drama films

- 1960s high school films

- British coming-of-age drama films

- British high school films

- British teen drama films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Biographical films about educators

- Films about teacher–student relationships

- Cultural depictions of British people

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films based on British novels

- Films directed by James Clavell

- Films set in London

- Films shot at Pinewood Studios

- Films shot in London

- Films with screenplays by James Clavell

- Films scored by Ron Grainer

- 1967 drama films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s British films